These lecture notes https://jdc.math.uwo.ca/l. (That's an "ell" at the end.)

Today we cover Section 2.1. Read Section 2.2 for next class. Remember that the text gives more examples and explanation than I can give in a lecture. Work through suggested exercises.

Homework 2 due today at 11:55pm. Homework 3 will also be on WeBWorK and will be available Saturday.

Math Help Centre: M-F 12:30-5:30 in PAB48/49 and online 6pm-8pm.

Regular office hours: Mondays, 3:30-4:30, MC130 (Middlesex College) and Fridays, 2:30-3:30 in the Math Help Centre. (But on Monday, Sept 23, I have to change it to 9:30-10:20am.) Drop by with any questions!

Definition: The cross product of $\vu$ and $\vv$ is the vector $$\kern-6ex \vu \times \vv := [ u_2 v_3 - u_3 v_2,\ u_3 v_1 - u_1 v_3,\ u_1 v_2 - u_2 v_1]. $$

Theorem 6-2: $\vu \times \vv$ is orthogonal to both $\vu$ and $\vv$. That is, $\vu \cdot ( \vu \times \vv ) = 0$ and $\vv \cdot ( \vu \times \vv ) = 0.$

Note: The cross product only makes sense in $\R^3$! It can be used to find a normal vector to a plane when you know two vectors $\vu$ and $\vv$ in the plane.

Note 6-3: If the line was in $\R^2$ and had been described in normal form, one could instead compute $\| \proj_\vn(\vv) \|$, which saves one step.

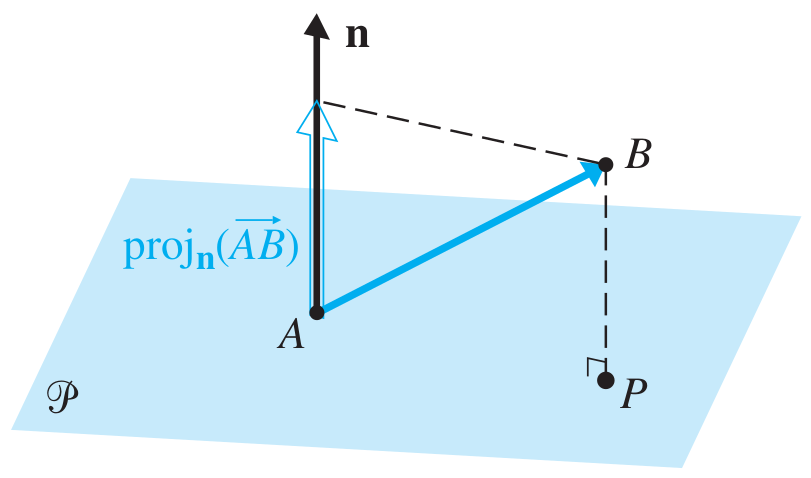

Let $\mathcal{P}$ be a plane through the point $A$ with normal vector $\vn$

and let $B$ be any point.

Then from the figure

$$ \kern-6ex

d(B, \mathcal{P}) = \| \proj_\vn(\vv) \| = \frac{|\vn \cdot \vv|}{\|\vn\|},

$$

where $\vv = \overrightarrow{AB}$.

Let $\mathcal{P}$ be a plane through the point $A$ with normal vector $\vn$

and let $B$ be any point.

Then from the figure

$$ \kern-6ex

d(B, \mathcal{P}) = \| \proj_\vn(\vv) \| = \frac{|\vn \cdot \vv|}{\|\vn\|},

$$

where $\vv = \overrightarrow{AB}$.

Definition: A linear equation in the variables $x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n$ is an equation that can be written in the form $$ a_1 x_1 + a_2 x_2 + \cdots + a_n x_n = b , $$ where the coefficients $a_1, \ldots, a_n$ and the constant term $b$ are constants.

Linear equations: $$ \kern-7ex \begin{aligned} 2x - 5y\ &= 10, & r + \frac{1}{2} s\ &= 0.5 t - 2, \\ x\ &= 0, & \quad x_1 - \sqrt{2} \, x_2 - (\sin \frac{\pi}{5}) \, x_3\ &= 0 . \end{aligned} $$ Non-linear equations: $$ \kern-7ex x y + z = 1, \quad x^2 + y^2 = 2, \quad \sin(x) = 0, \quad 2^y + z = 16. $$

A solution to $ a_1 x_1 + a_2 x_2 + \cdots + a_n x_n = b $ is a vector $[s_1, \ldots, s_n]$ such that the equation is true when we substitute $x_1 = s_1, \ldots, x_n = s_n$. For example, $[ 10, 2 ]$ is a solution to $2x-5y=10$.

When a linear equation has two unknowns, its solutions form a line in $\R^2$. (The linear equation is the general form of this line.) To describe the solutions in parametric form, we can solve for one of the variables in terms of the other.

For example, for $2x-5y=10$, we can write $y = \frac{2}{5} x - 2$. If we set $x$ to a parameter $t$, we get parametric solutions $$ \begin{aligned} x\ &= t \\ y\ &= \frac{2}{5} t - 2 \end{aligned} $$ or, more concisely, $[t, \frac{2}{5} t - 2]$.

When there are three variables, the solutions form a plane, and it can be described in parametric form by solving for one variable in terms of the other two.

The same works when there are $n$ variables: we can solve for one in terms of all of the others, and get a solution with $n-1$ parameters.

Definition: A system of linear equations is a finite set of linear equations, each with the same variables. A solution to the system is a vector that satisfies all of the equations.

Example 7-1: $$ \begin{aligned} x + y\ &= 2\\ -x + y\ &= 4 \end{aligned} $$ Is $[1, 1]$ a solution? How about $[-1, 3]$? How can we find all solutions? What's happening geometrically? Board.

Example 7-2: $$ \begin{aligned} x + \phantom{2} y\ &= 2\\ 2 x + 2 y\ &= 4 \end{aligned} $$ Is $[1, 1]$ a solution? How about $[-1, 3]$? How can we find all solutions? What's happening geometrically?

Example 7-3: $$ \begin{aligned} x + y\ &= 2\\ x + y\ &= 3 \end{aligned} $$ Is $[1, 1]$ a solution? How about $[-1, 3]$? How can we find all solutions? What's happening geometrically? Board.

A system is consistent if it has one or more solutions, and inconsistent if it has no solutions. We'll see later that a consistent linear system always has either one solution or infinitely many.

Example 2.5: Similarly, a large system such as $$ \begin{aligned} x - y - \phantom{3} z\ &= 2 \\ y + 3 z\ &= 5 \\ 5 z\ &= 10 \end{aligned} $$ is easy to solve, because of its triangular structure. The method is called back substitution: $$ \begin{aligned} z\ &= \cyc{ex2.5-1}{2}\\ y\ &= \cyc{ex2.5-2}{5 - 3z = 5 - 6 = -1}\\ x\ &= \cyc{ex2.5-3}{2 + y + z = 2 - 1 + 2 = 3.} \end{aligned} $$

Let's see how a general system can be converted into a system with a triangular form.

Example 2.6: We'll solve the system on the left

$$

\kern-6ex

\begin{aligned}

\ph x - \ph y - \ph z\ &= 2 \\

3 x - 3 y + 2 z\ &= 16 \\

2 x - \ph y + \ph z\ &= 9

\end{aligned}

\qquad\qquad

\bmat{rrr|r}

1 & -1 & -1 & 2 \\

3 & -3 & 2 & 16 \\

2 & -1 & 1 & 9

\emat

$$

but to save time, we can write it as the augmented matrix on the right.

Today, we'll show the equations as well.

To put it into triangular form, the first step is to eliminate the $x$s in equations 2 and 3. We write $R_i$ for the $i$th equation or the $i$th row of the augmented matrix.

Replace $R_2$ with $R_2 - 3 R_1$: $$ \kern-6ex \begin{aligned} \ph x - \ph y - \ph z\ &= 2 \\ 5 z\ &= 10 \\ 2 x - \ph y + \ph z\ &= 9 \end{aligned} \qquad\qquad \bmat{rrr|r} 1 & -1 & -1 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 & 5 & 10 \\ 2 & -1 & 1 & 9 \emat $$ Replace $R_3$ with $R_3 - 2 R_1$: $$ \kern-6ex \begin{aligned} \ph x - \ph y - \ph z\ &= 2 \\ 5 z\ &= 10 \\ y + 3 z\ &= 5 \end{aligned} \qquad\qquad \bmat{rrr|r} 1 & -1 & -1 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 & 5 & 10 \\ 0 & 1 & 3 & 5 \emat $$ Now we can exchange rows 2 and 3, to end up in triangular form: $$ \kern-6ex \begin{aligned} \ph x - \ph y - \ph z\ &= 2 \\ y + 3 z\ &= 5 \\ 5 z\ &= 10 \end{aligned} \qquad\qquad \bmat{rrr|r} 1 & -1 & -1 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 & 3 & 5 \\ 0 & 0 & 5 & 10 \\ \emat $$ Hey! This is the system we solved earlier, so now we know that the solution is $[3, -1, 2]$.

This system and the original system have exactly the same solutions. (Explain.) We say they have the same solution set and therefore that they are equivalent systems.

True/false: The equation $$ \frac{x}{\sin(2)} + y = z $$ is linear.

True/false: The system below has no solutions: $$ \begin{aligned} 2 x + 3 y + 4 z\ &= 7 \\ 4 x + 6 y + 8 z\ &= 9 . \end{aligned} $$

Alternatively, one can subtract twice the first equation from the second to get $0 = -5$, which has no solution.

True/false: The system below has a unique solution: $$ \begin{aligned} 2 x + 3 y + 4 z\ &= 7 \\ 4 x + 6 y + 8 z\ &= 14 . \end{aligned} $$

Question 7-4: Solve the system below geometrically and algebraically: $$ \begin{aligned} 2 x + 3 y\ &= 2 \\ x + 2 y\ &= 2 . \end{aligned} $$

Algebraically: subtracting half of the first equation from the second gives $$ \begin{aligned} 2 x + 3 y\ &= 2 \\ \frac{1}{2} y\ &= 1 \end{aligned} $$ Now we apply back substitution. The second equation gives $y = 2$, and then the first equation gives $x = -2$. (Check that this satisfies the original equations!)

Question: How many solutions does the system $$ \begin{aligned} 2 x + 3 y\ &= 2 \\ x + 2 y\ &= 2 \\ x + 4 y\ &= 2 \end{aligned} $$ have?

Geometrically, this corresponds to three lines which enclose a triangle.